Lama Medical Information

Normal Vital Parimeters for the Llama

Resting body temperature: 37.5-38.9 C

(99.5-102 F)

Heart rate: 60-90 bpm

Respiratory rate: 10-30/minute

Gastric motility: 3-4 contractions/minute (This is more rapid than with ruminants). Palpation of the first compartment is difficult and auscultation will be necessary to assess motility.

Gall bladder: Not present

In addition to the genitalia, male and female can be differentiated by the presence of canine teeth in the male and the thicker neck and thicker skin (0.5 inch) overlying the jugular veins of the male. This thickened skin and the wool on the neck severely complicate the process of jugular vein catheterization. Additionally, the vessel traverses differently compared to farm animals, making it very difficult to identify. These differences from other species should be kept in mind before one gets completely frustrated. The course of the vein as it passes medial to the cervical vertebral transverse processes in the mid-portion of the neck leaves less length available. The jugular may be balloted or stroked about 8 cm below the angle the ramus of the mandible makes with the neck. The jugular does not stand out as it does in the ruminants when occluded. Another site to try is cranial to the point of the shoulder. The skin is thinner; however, restraint is critical to prevent injury to the phlebotomist; the carotid is closer to the jugular in this area. The llama vertebral pattern has: 7 cervical, 12 thoracic,7 lumbar, 5 sacral and 16-20 caudal vertebra.

Llamas tend to toe out. The foot is padded but the horny nail may require trimming on a routine basis. A scent gland is located on the lateral side of the rear leg. Some people find the scent emitted to be too similar to the odor of mice.

Llama erythrocytes are ellipsoids that pack into a smaller volume, resulting in a lower PCV. Hematology parameters may be found in the references given on page one and should be noted if evaluating llama bloodwork from a lab without llama normals established.

Llamas should be encouraged to graze. They thrive on timothy type hays. All llamas should receive small quantities of llama chow (Mazuri) on a daily basis as the most complete knowledge we have about llama nutritional requirements has been formulated for delivery by that feedstuff (e.g. vitamin and mineral requirements, etc.). Don't feed llamas sweet feed or horse chow. Don't let them get too fat, as you predispose them towards heat stress and many other problems.

Remember that no drugs are currently approved for use in llamas in the United States . This includes vaccines, anthelmintics, antibiotics, etc. Everything is extra-label use, as of this writing.

Restraint

The level of restraint needed in working with llamas varies depending on the amount of handling the animal has received from the owner. The llama naturally resents having its head and neck approached unless it has been desensitized to human touch. Most llamas can be easily taught to halter lead and this should begin at an early age (4-8 months). Juvenile llamas can be restrained by either cradling them in arms or physically holding them down in lateral recumbency. Straddling these animals while in the cush position can also be an effective restraint technique. Adult llamas which have been adequately handled usually will tolerate a physical examination of the head when approached in a calm, caring fashion.

Anxious animals require the use of alternative restraint methods. There are several varieties of chutes available to physically restrain llamas that will make physical examination much more acceptable to all involved. Chemical restraint is a viable option to consider for a variety of procedures. Consult your veterinarian for appropriate sedations. Ear twitching is sometimes effective for brief procedures but this technique is not always acceptable by owners. The method of restraint should vary and be appropriate to offer comfort to the animal, facilitate ease in performing the procedure by personnel and the owner.

Common Health Issues

Parasites

Many parasites can affect llamas. Nematode parasites include Haemonchus, Trichostrongylus, Camelostrongylus, Nematodirus, Strongyloides, Capillaria, and Oesophagostomum. A fecal is important for identification of the problem and to estimate the parasite load. Clinical signs are similar to other species affected by these parasites.

The meningeal worm, Parelaphostrongylus tenuis, causes few problems in the natural host, the white tailed deer; however, in an aberrant host such as the llama, clinical signs are consistent with the area of migration through the spinal cord: lameness, paralysis, blindness, etc. Frequent deworming and maintaining a deer-free llama enclosure is recommended; also, avoiding areas with heavy snail or slug populations is useful.2 There is no antemortem procedure to definitively diagnose meningeal worm migration as the cause of neurological signs in an animal. Very few llamas have been successfully treated following infection with this parasite. The treatment protocol is costly, requires much time and patience, and a successful outcome is not guaranteed.

Tapeworms are found in llamas. Usually clinical signs are minimal. Coccidia, giardia and toxoplasma have been reported as well as sarcocystosis. The common liver fluke (Fasciola hepatica) can cause severe disease in the llama.

Anthelmintics have been used based on extrapolation from other species. Common sense husbandry practices such as avoiding contamination of food and water sources by llamas or carnivores (dogs, cats) and quarantining new arrivals can be important in parasite control.

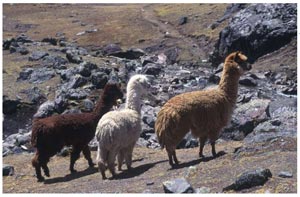

Heat Stress Heat Stress

Heat stress in llamas is a real threat, especially those kept in our area. Llamas are animals of altitude and require careful management to prevent heat-related problems. Heavy hair coats, obesity, stress from sickness, infections, and forced recumbency from injuries or fractures make llamas more susceptible to heat stress. Southern humidity is particularly difficult to tolerate. Since the llamas main area for heat loss is the thin wooled area on the ventral abdomen, any problem resulting in recumbency will predispose the llama to heat stress. Unfortunately, a severe case of heat stress will result in the animal becoming recumbent. Southern llamas commonly have the wool around their abdomens cut short in a poodle cut. Extremely nervous animals may require mild sedation. Owners should consult their veterinarian for assitance with these cases.

Animals that are reluctant or are unable to rise should be carefully examined. An elevated rectal temperature will usually be evident. Weakness, anorexia, and neurologic signs (including convulsion and respiratory arrest) may be noted. Animals may eventually lose their central thermoregulatory ability. CK will be elevated. Treatment is to correct the body temperature and support the animal physiologically. Spraying the animal with cold water may be useful but should be directed towards the ventral abdomen. If whole body wetting is attempted, make certain the droplets reach the skin surface because retention of droplets on the external surface of the wool will only make the animal feel hotter. If convulsions are occurring, ice should be applied to the back of the head. Correction of the electrolyte abnormalities and prevention of muscle damage due to recumbency is important. It may be necessary to sling or lift the animal to encourage standing.

Colic and C3 Ulcers

Llamas are prone to third compartment ulcers and all the other acute abdominal problems from which bovine suffer. These disease processes may cause the llama to cast itself, roll on its back, kick at its side, or lie continuously in lateral recumbency. Radiographs, electrolyte assessment, abdominal taps and rectal palpation of adults may help make a decision before or against acute abdominal accident requiring surgery. Since stress (e.g. being the lone llama on a farm, show schedules, competition for feed, etc.) can predispose to C3 ulcers, one should take into account the llama's recent past history. Acute abdominal crisis is often complicated by secondary heat stress so keep these animals as cool as possible. C3 ulcers have been reported to respond to intravenous or oral omeprazole; standard H-2 blockers are not as effective.

Blood Collection

For blood collection, the most common site used is the jugular vein. This can be performed on the right or left side, but care should be taken not to traumatize vital structures (esophagus, trachea, nerves, carotid arteries). For smaller amounts of blood, an ear or tail vein may be used. Intravenous catheterization is best performed in the right jugular vein. In older animals the fiber and skin are usually thick, making visualization and palpation very difficult. The vein is located just ventral to the lateral spinous process of the cervical vertebrae. It is necessary to make a skin incision to avoid damage to the catheter. The skin may be 1/4" thick here. There are a series of jugular valves which make catheterization even more difficult. Never attempt to collect a blood specimen. This procedure should only be attempted by your veterinarian.

Treatments and Procedures

Injections:

Sites for intramuscular injections in llamas are limited due to their poor muscular tone. The caudal thighs and anterior pectoral muscles are commonly used. If frequent injections are needed, it is best to rotate muscles to prevent soreness. It is better to go subcutaneously whenever this option is available.

Oral Medications:

In administering oral medication, this clinician has found it best to administer liquids via stomach tubes (this may help reduce the chance of being spat on by the animal). Some llamas tolerate this procedure better than others do. A mouth speculum can be readily made with a 12-cc syringe case to fit crias simply by cutting off the tip. Always be sure that the tube is in proper location within the esophagus or stomach before administering oral medications.

Feet:

When it comes to working on feet, most llamas accept trimming and examination under normal circumstances. However, unhandled or diseased patients may be challenging to work with, and they may attempt kicking or stomping. Many usually cush to avoid having to feet lifted. Routine toe trimming and handling is necessary to avoid foot problems.

Reproduction and the Significance of the Poop Pile

Llamas urinate and defecate in a common area. This is one reason llamas are particularly popular pack animals in the Wilderness Areas of the Western mountain ranges. In the most tightly controlled of these areas, all fecal matter must be packed back out. This is much easier when the feces are small dry pellicles deposited in one spot. This also contributes to their popularity as domestic pets because pasture cleanup is relatively easy.

Females are induced ovulators. Usually the males are re-introduced to the female about 12 days following parturition. At this time, the male usually will run to the poop pile and sniff. If any open female is present, he will immediately recognize progesterone in her urine and will unwaveringly run right to her. The female will run from the male and he will pursue her for a short time, vocalizing continuously (this sound is called an ortle). If he has made an error and she is pregnant, she will spit him off repeatedly during this process until he stops and leaves her alone. If she is not pregnant, she will allow herself to be mounted and will cush. Mating occurs in the cush position. The legs of the male squeeze tightly about the body of the female. The sound of the ortle, the cush position, and the pressure exerted by the limbs of the male are all necessary to induce ovulation. Artificial insemination (AI) has not been particularly successful in the past and this has helped to maintain the individual financial value of the males. Current methods using human chorionic gonadotrophin (HCG) or gonadotrophin releasing hormone (GNRH) and breeding with a vesectomized male are making AI a more feasible alternative.

It was previously believed that females could only carry one viable fetus (as a singlet) and only in the left horn of the uterus. It was also thought that all right horn pregnancies and twin pregnancies would abort. There have been several successful twinning situations over the past years that prove this theory wrong. Ultrasound can be used to diagnose pregnancy. Rectal exams can be performed by those with smaller hands; sedation makes repro work easier for some.

The baby llama is called a cria and weighs 25-35 lbs. Normal gestational length is 335 to 360 days. Placentation is described as diffuse and epitheliochorial, as in the mare. The cria and dam hum to each other; this vocalization begins immediately after birth and probably helps the neonate locate its mother very rapidly. In the wild, most cria are born in the daytime because they must be dried off and capable of thermo-regulating before the approach of the chill cold of night in the Andes. Like other herbivores, colostrum must be ingested to provide antibodies to the immunocompromised neonate. Goat colostrum can be substituted for orphans; llama plasma can be purchased commercially. The biggest mistake made in administering plasma to neonates is that large animal veterinarians forget the small size of the cria and may administer such large quantities that pulmonary edema results. Males are subservient to neonates and pose no threat to them until they begin to experience puberty.

Neonates:

Constipation can occur due to meconium impaction. Diarrhea can develop from overfeeding (especially when being bottle-fed). Beware of Berserk male syndrome, which occurs when male bottle-fed crias become bonded to humans. Later, at puberty, the llama will display aggressive behavior towards humans as they would otherwise normally demonstrate towards other llamas.

Behavior, Spitting and 'That Berserk Male Thing'

Occasionally lamas do spit and can be fairly accurate at spewing gastric contents for 3-6 feet when annoyed or restrained; however, most llamas are well-behaved and easy to handle. If verbally reprimanded, they can be educated NOT to spit off humans. Remember, the smell washes off after only a few showers. Spitting off is used to control over-exuberant males, protect one's feed from others, or if another llama just gets too close.

Males fight viciously using their canine teeth to try to lacerate the jugular region and may inflict an unpleasant bite during mating. For this reason, total canine tooth removal or repeated use of gigli wire and or dermal can be used to smooth the teeth off at the gumline. Canines will frequently grow back in uncastrated males.

Llamas can kick and bite other llamas or people. An occasional animal, particularly orphaned males raised by hand, become imprinted on humans as youngsters, and demonstrate dangerous behavior towards humans. This is sometimes called the 'beserk male syndrome'. These animals are extremely dangerous. Castration does not affect the behavior of males, and owners are usually forced to euthanize the animal. Be cautious when raising orphans, especially males, or overhandling youngsters. Be very cautious if asked to work with a rogue male llama. The majority of llamas are quiet, serene animals with kind dispositions, and no more dangerous than any other animal of its size. All llamas should be trained to be led by halter and taught to cush.

Other Diseases in Lamas

Clostridial infections:

Enterotoxemia types A, C and D are known to occur in llamas. Type A has recently become a suspicious cause of acute death in North American llamas, and is a serious problem in South American animals. The clinical signs of enterotoxemia caused by types C and D are similar to the corresponding disease in small ruminants. Type C is more often seen in younger animals, with type D in older animals on a high plane of nutrition. Tetanus has been reported. Llamas do not appear to be significantly susceptible to tetanus.

Vaccination against the clostridial disease is practiced by many owners and veterinarians. The 8-way vaccine products may result in a vaccination site reaction but is currently the recommended vaccine of choice in lamas.

Rabies:

Llamas can, and do, get rabies. Many owners request vaccination. If you vaccinate, use only killed products.

Equine herpes virus:

EHV-1 was diagnosed in a herd of llamas exposed to zebras. It is known to cause retinal degeneration resulting in blindness in lamas. Owners may request vaccination. Again, there is no efficacy known for equine vaccines in the llama and care should be used.4 Only killed products should be used. Pneumabort - k has been used with some success in outbreaks areas.

Leptospirosis:

Leptospira abortion in llamas has been reported. 5 Lepto bacterins in multiple serovar combinations are used in llamas. There is uncertainty as to weather or not they really work.

Tuberculosis:

TB has been a difficult problem in the llama industry as well on the regulatory front. Tuberculin testing of the caudal tail fold is not considered reliable. Currently the preferred site for testing is with 0.1 ml PPD bovis in the fiberless postaxillary region. The standard 72 hour post injection reading in required. Llamas are susceptible to tuberculosis and therefore may be required to be tested for transport, sale or show. Contact the state authorities for the latest update and procedures. This is a reportable disease.

Anthrax:

Clinical disease has been reported in llamas. Signs appear to be similar to other mammalian species. Treatment with tetracycline or penicillin can be successful if diagnosed early. Death due to anthrax vaccination has been reported.6

Johnes:

Johnes disease can cause chronic wasting disease in lamas as in ruminants. Depending on the degree of illness, diarrhea may or may not be present. Supportive therapy and treatment with clofazamine may help reduce clinical signs and increase survival time with long life therapy. Further study is needed on this disease in lamas. Consult your veterinarian for recommendations.

West Nile:

West Nile disease has been diagnosed in lamas. It may be useful to perform vaccination in an attempt to prevent these diseases in high risk areas of the country. There is no current information on the efficacy of this vaccine when used in lamas. Consult your veterinarian for recommendations.

Encephalitis:

Eastern and western encephalitis has been diagnosed in lamas. It may be useful to perform vaccination in an attempt to prevent these diseases. There is no current information on the efficacy of this vaccine when used in lamas.

Foot and Mouth:

Very rare in Llamas.

|